Press Wireless History

In 1920, dissatisfied with the cost and timeliness of news transmission by international telecommunications companies a group of publishers formed the American Publisher's Committee on Cable and Radio Communications (APC), and after a year's work, the group decided to go into the communications business themselves. Their first operation was a dedicated radio link from London, England to Halifax, Nova Scotia, using long-wave equipment provided by the British Post Office, left over from WWI. Halifax was chosen not only because of its excellent location for radio reception from England, but also because large communications companies prevented APC from purchasing equipment in the US. Messages received at Halifax were transmitted by telegraph to US addresses, entailing delay and extra cost. APC began discussions with the Federal Radio Commission (FRC, later the FCC) for use of "transoceanic" frequencies (above 6 Mc), and on May 24, 1928, the FRC allocated 20 frequencies to various press interests. Arguments amongst the various press companies about frequency allocation led the FRC to order the companies to form a public utility for the purpose.

Press Wireless Corp was founded in 1929 to serve this purpose, capitalized at $1M. The companies that initially owned stock in Press Wireless included

with no one company allowed to own more than 20% of Press Wireless' shares. Further wrangling with newspaper companies not original part of Press Wireless complicated operations until February 1931, when the FRC clarified the rules under which the company was to operate.

PreWi's first station WJK was built in Needham, Mass in 1930, and was used to communicate with the existing Halifax station. Long-wave receiving facilites were set up at WJK to intercept transmissions from London. When a message was received at WJK, Halifax was notified, to avoid duplication, saving telegraph charges, and speeding up traffic delivery to US addresses.

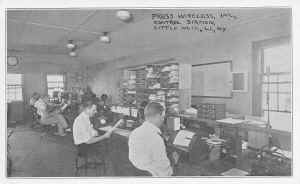

From this point PreWi expanded its facilities, constructing a transmitting station on a 185 acre site at Hicksville and a receiving site at Little Neck, Long Island in 1930 (the Little Neck "control station" shown in the photo below).

The receiving station at Little Neck contained up to a dozen or more operating positions, and this facility was in constant use through the 1940's. The transmitting site opened for full service in 1932. By 1933 the company had as many as five callsigns, all beginning with "WJ" (WJO, WJP, WJQ, WJS, and WJU). At the time, each frequency was allotted a different callsign, regardless of which transmitting equipment was in use. Oddly one of the shortwave stations at Hicksville had the four-letter callsign "WRDK", presumably because PreWi management had in mind becoming a broadcaster, and indeed that proved to be the case.

The Hicksville transmitters were originally rated at 10KW, but later transmitters operated at lower power, some 5KW and one 500W rig. At least one 40KW transmitter was in operation during WWII, manufactured by Press Wireless itself. A Time Magazine article stated that there was a 100KW transmitter in operation by 1939 at the facility.

Stations were built in San Francisco and Honolulu in 1932. PreWi's stations often used vacuum tubes imported from foreign countries to circumvent US patent restrictions. The Honolulu station used callsign KDG, and the Honolulu/San Francisco link used frequencies 7340, 7355, 7370, 7820, 7835, 7955, 15610, 15640, 15670, 15730, 15760, 15880 and 15910 Kc.

At about the same time, PreWi negotiated an unprecedented lease agreement with the French Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs for transmitters and receivers located in Paris. The agreement allowed PreWi to conduct operations from a newly opened Paris office. Many American newspapers began to use the Paris-to-NY service provided by PreWi, centralizing their dispatches from Paris.

The company's network began to circle the globe (see map below), and customers included Associated Press, Agence France Press, Reuters (Britain), ANSA (Italy), DPA (Germany) and others.

As the company grew, it assembled a expert engineering and production staff and began building equipment itself. Many of the new PreWi engineers were radio amateurs, including Ray de Pasquale, who became the company's Director of Manufacturing in the late 30's. PreWi was often the first to develop and put into service improved communications technology, and this included FSK for both RTTY and Facsimile (PreWi's FSK design were featured in a Nov 1944 Electronics Magazine article "Frequency-Shift Radiotelegraph") . PreWi also pioneered frequency multiplexing for RTTY with its "Duo-Plex" system.

By the late 30's the company was manufacturing its own HF transmitters with power output up to 50KW, and it also built receivers including the PW Model C (fixed frequency receiver) that provided reception for the company's multi-point press-casts and photo-casts by various new agencies.

Service during this time period covered 62 countries and carried 450 million words of text, 36,000 fax photos, and 83,000 minutes of voice programming per year. It operated 47 HF transmitters at its Centereach, Long Island facility and 10 at Belmont, CA. The 500-acre transmitting antenna farm at Centereach supported over 70 antennas of various types, both omni-directional and directional. The Long Island and California facilities pioneered and operated a large array of diversity receiving equipment.

Press Wireless' global network for the first time provided nearly instant news delivery via newspapers, broadcast stations, and bulletin boards. Although primarily a news dissemination and broadcasting organization, PreWi also provided communications between ground and trans-Atlantic passenger aircraft including all ground facilities for Aeronautical Radio, Inc, which served airlines entering and leaving the US. The company also won a competitive bidding process to transmit US Weather Bureau meteorological facsimile maps from Washington DC to European and Pacific destinations. PreWi provided duplex radio teletype service for the United Nations between New York, Geneva, and Leopoldville. The State Department also depended on PreWi's teleprinter service to Montevideo, Uruguay, which provided 97% up-time, the highest rate of service of any the State Department operated around the world.

PreWi's California transmitting and receiving facilities provided a unique service to Japan and China, accommodating the two ideographic languages using facsimile service, since at the time, teleprinters could not support these languages.

PreWi substantially improved communications between Moscow and New York, often adversely affected by propagation problems across the North Pole. The company developed alternate routes that made use of automated repeaters, one via its Montevideo station and the other via California and a Soviet station in Khabarovsk, Siberia. At the time, these were the only circuits of their kind.

PreWi was the first company to offer multiple-address or multiple-destination transmission of news, referred to by the FCC as "scheduled transmission service". By the 40's, the company had 700-800 customer accounts, not including 250 multiple-address subscribers.

In addition to press message traffic, PreWi entered the broadcasting business in the 1930s, using transmitters located at Hicksville, Long Island. Initial broadcast transmissions were made in 1935 using the callsign W2XGB, using a 500W transmitter, though subsequently, broadast transmitters of 1KW and 5KW were used. Often PreWi's broadcasts were relays of programming from WOR, a 50KW station in New York.

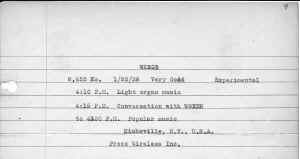

QSL's from Press Wireless indicated callsign W2XGB by the late 30's, stating a 5KW power level. Station W2XDH was initially rated at 1KW, but made use of a 10KW station beginning in December 1940. PreWi was quite happy to acknowledge SWL signal reports, as shown below. This report, from a listener in nearby New York City, cannot have had much value to the company, but politely answered in any case!

Original signal report from Louis Ragazzini. |

|

Hicksville transmitters were sometimes used in the pre-war years for relays of special radio program broadcasts to Europe, the Caribbean, and South America, usually in English and Spanish, and these were typically taken from regular NBC broadcasts.

In a particularly odd experiment, and in cooperation with WOR, an attempt was made to communicate with the planet Mars. A 100KW shortwave transmitter at Hicksville was beamed skyward in August 1939. Evidently no reply was heard.

In 1942, a Hicksville shortwave station operating as WCW began test broadcasts relayed from the Mutual Radio Network, this in anticipation of regular relays for the Voice of America. These regular VOA relays began in April 1942, and many broadcasts in many languages were transmitted to Africa, Europe, Latin American and the Pacific during the next 3 years. These relays were intended for direct broadcast to listeners. The broadcasts, and sometime news reports, were intended for American armed forces as well.

Starting in March 1943, VOA relays from PreWi Hicksville were identified on-air with regular 4-letter callsigns, just like regular broadcast-band stations in the US. The known callsigns included WKCS, WKLJ, WKRB, WRKD, WKRI, WKRO, WRKX, WKTM, WKTS, WLIO. These stations were evidently intended for program service to particular areas, though not to specific transmitters, nor to particular shortwave frequencies. At the same time, the usual 3-letter callsigns were still in use for PreWi's various types of transmissions, including broadcasts.

VOA and Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) broadcasts ended late in 1944. And, 13 years later, the history Hicksville station was closed, and a new station opened at Centereach. During the 30's, PreWi's Hicksville station issued a few QSL cards that included a photo of their transmitter building, and listing the callsigns W2XGB and W2XDH. No QSL's were issued from the 3-letter callsigns.

As the war approached, Press Wireless was the only American communications carrier operating in France during the summer of 1940. As the Germans crossed the border into France, PreWi, by previous arrangement with the French government, moved their operations to Bordeaux, then to Tours, providing the only communications between France and the US and England. During this period, PreWi not only handled their usual press traffic but also carried government and banking messages. On July 13, 1940, the company established a Vishy station.

PreWi's station in Shanghai continued operation even as the Japanese were invading the city in August 1937, and they continued operation until discovered by the Japanese Army. It is said that as the Japanese came in the front door, the radiomen went out the back door!

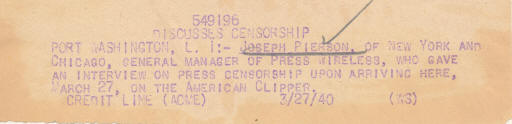

Censorship was clearly going to be a problem for the company as they reported on the war effort. Well in advance of the US entering WWII, the company was already discussing the issue with the government. The photo and caption below became a newspaper story in March 1940. Joseph Pierson was the General Manager for PreWi at the time. A face that would frighten children...

|

|

After the US entered the war, press reports from the various fronts were handled in a way dictated by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the FCC, and the Board of War Communications. PreWi got a bit of a 'raw deal' when it was barred from North Africa and later from Italy. Mackay Radio Corp received exclusive rights in North Africa and RCA in Italy, as the Joint Chiefs stated that each new circuit into the war zones be limited to one carrier. The FCC denied several applications by PreWi to operate at various points in the war zones, including Algiers, Oran, and Tunis.

To deal with this situation, the company filed a petition to the FCC on July 28, 1943 to modify its license to expand its authority from fixed public press service to fixed public service. Other communications companies objected, stating the PreWi was attempting to become a general communications company. PreWi amended its application to request fixed public service only on circuits restricted to one American carrier because of war considerations, and only during the time when the one-carrier restriction applied. The FCC granted the petition. By 1944, for example, Press Wireless was operating from Palermo Sicily. See The Palermo Lyre for an example of a dispatch from that station. At this point the FCC finally designated Press Wireless along with Mackay to handle the copy of war correspondents during the upcoming Normandy invasion.

During the war years, Press Wireless greatly expanded its manufacturing capability, producing radio transmitters and other gear both for itself and for the US military. The Secretary of War conferred the Army-Navy Production "E" Award three times on the company for outstanding achievement in producing communications equipment for the war effort. War-time ads from PreWi touted the company's defense efforts (in this case the 40kW transmitter (center) and the AN/FRR-3 and -3A diversity receivers (right)) and quite justifiably mentioned the prestigious "E" awards.

War correspondents assigned to the Normandy Invasion were greatly surprised just a week after the beginning of the invasion, June 13, 1944, when they discovered that they could communicate directly with their home offices back in the US. A portable radio station had been shipped by Press Wireless from New York to England, and from there the station was loaded onto an LST, beached at Normandy, and installed on the Allied lines on June 6, 1944. (It appears that PreWi shipped several stations from Long Island to Europe--at least one of them is still sitting on the bottom of the Atlantic off Long Island, the victim of a German U-boat). The station was initially located in a horse pasture near the Normandy shore. 3,000 miles away radio operators at Baldwin, Long Island began searching for signals from the newly-established station. Press Wireless representatives in Washington and London had been trying for months to get a frequency assignment, but the delays were endless.

These difficulties did not slow down Myron Earl, who was in charge of the Normandy station. With copy flooding in from war correspondents, Earl decided it would be better to get onto the beach and worry about frequencies later. As traffic increased, he decided to use a frequency already authorized for PreWi's San Francisco circuit, though he had doubts about whether his 400W transmitter would be able to work reliably.

Baldwin operators noticed that the San Francisco transmitters was suddenly being jammed by another station, and ordered San Francisco off the air. Then the station call letters "PX", the Normandy station, were clearly received. On the next day, June 13, Press Wireless accepted a dispatch from its first Normandy customer, Henry T. Gorrell, of United Press. New York received the copy a few minutes later. In the first week of operation, PX sent 200,000 words to the New York offices and thence to press associations, newspapers, and magazine whose correspondents had filed copy.

PreWi's difficulties with the government were not over, however. An order from headquarters forced PreWi to suspend all operations. Only after correspondents cabled General Montgomery and Eisenhower, and President Roosevelt, was the order rescinded. Operations were closed down for nearly 30 hours.

Station PX followed closely behind the Allied advance, as they continued to move through France and Belgium. The operators became adept at rapid setup and tear-down of their antennas, with due attention to camouflaging their truck. At no time did Press Wireless refuse copy. British correspondents filed dispatches to London through New York faster than they could via a direct route. The operators sped up service to 90,000 words per day by radio telephone and radiotelegraph. Not long after the station became operational in France, voice operation was brought up. American radio networks picked up the programs originating from the trusty 400W transmitter and re-broadcast them. PX was the first radio station to operate in the newly-liberated Paris, providing the first news from the city.

From Belgium, Station PX proceeded to Berlin, arriving in July 1945. Direct radio telegraph service to New York was established, and the first message was sent to the American Broadcasting Company in New York by Donald C. Coe, one of its Berlin correspondents. Facilities for radio photo and radio telephone were installed shortly thereafter.

After a permanent Press Wireless station was installed in Berlin, Station PX moved to Nuremburg in November 1945. The very same 400W frequency-shift transmitter was transported by the same Army truck (see photo above) that unloaded it from an Army transport ship on the Normandy beachhead. Roughly 500,000 words of press traffic were handled by the station during the Normandy Invasion.

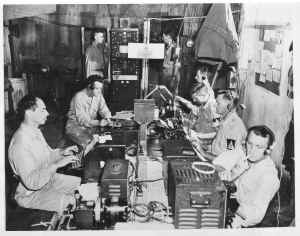

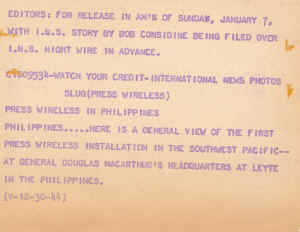

Press Wireless was also active in the Pacific theatre of operation. Another mobile station, Station PZ, accompanied the invasion forces into the Philippines, beginning operations on November 14, 1944. The station, situated on Leyte, was manned by a crew of 9 and housed in a sand-bagged and camouflaged structure.

|

|

| Photo of PreWi Leyte operations bunker (Dec 1944) | Caption on rear of photo. |

Though not truck mounted, Station PZ could be dis-assembled and moved very rapidly. It sent the first commercial news messages from the Philippines to the US since the Japanese invasion in 1941. Press Wireless mobile stations followed General MacArthur to Luzon and then into Manilla, transmitting news from the front to the Leyte station, for relay to the US. In the first 12 hours after the US entered Manilla, PreWi handled some 25,000 words of copy in this way. The Leyte station communicated with the company's station in Los Angeles, CA, and special land communications allowed dispatches to reach New York within 12 minutes of their filing on Leyte.

Operations in the Philippines presented special problems for the PreWi operators. In addition to constant rain, mud and heat, the paper tape used for RTTY communications became soggy and couldn't be properly punched. The PreWi crew had to employ some cleverness to make things work. An emergency oven, big enough to hold 25 rolls of tape, was quickly fabricated from a box, a spare heater, and a thermostat; this worked well, as it turned out.

From the Popular Mechanics article "Flashing the News from the Front" (June 1945), the Leyte crew is quoted as saying:

"We fondly refer to the transmitter as "Venice" and the operating center as "Hollywood and Vine". (This is in honor of the California home station.) The latter is in a dimly lighted corner of a concrete building. The walls are rough and water-stained. The tin roof serves as a ceiling. The floor is of cement and threaded with cracks. The atmosphere is damp and the high humidity results in troubles not often encountered at home.

In the corner of our "office" is the broadcast "studio". Constructed of wood and covered on the interior with tar paper and burlap, it is a far cry from the modernistic studios we knew back home. The microphone sets on a packing box. A kerosene lantern is the source of light as this is written. The windshield from a wrecked Ford passenger car serves as a window."

The first voice transmission for radio-network distribution was sent from this "studio" on December 23, 1945, using PZ's 400W transmitter. Its success is considered remarkable by radio engineers, skeptical of the ability of a 400W transmitter to send broadcast-quality audio across the Pacific.

During the war years, the importance of the company would be difficult to overestimate. For example, in 1942, PreWi handled 34% of outbound and 50.2% of inbound press wordage out of all American carriers. In 1943, the company transmitted 67% of the 4,875 radio photos transmitted that year, including 417 hours of multiple-address photo transmissions (PreWi being the only company to offer the service).

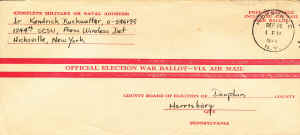

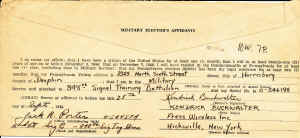

I came upon this odd little item relating to PreWi's war years: A Lieutenant Kendrick Buckwalter, assigned to the1244th SCSU (Service Command Service Unit, 848th Signal Training Battalion) evidently assigned to Press Wireless in Hicksville, Long Island) submitted an absentee ballot for the 1944 election. Below are scans of the envelope:

|

|

In July 1945, the company built a new manufacturing site in Long Island City, New York, as reported in the two photos and captions below. Since the war ended just a few months later, production at the LI City plant can hardly have begun in time to help the war effort, but the company still had the new plant on the books after the war.

| Photo by Drucker-Hilbert Co. 106 W. 43rd Street, New York 18, NY, Photo number 5722#4. Attached label says: "From Press Wireless, Inc. 1475 Broadway, N.Y., N.Y. MEN BEHIND THE NEW PRESS WIRELESS ENGINEERING AND ASSEMBLY PLANT in Long Island City are Left to Right, Ray H. dePasquale, Director of Manufacturing, Press Wireless, William Welsh, President of Welsh Brothers Contracting Company of Long Island City, Builder-Owner, and Salvatore Barone, Chief Manufacturing Engineer, Press Wireless." Sal Barone later went on to become the founder and president of Northern Radio in New York City. | Photo by Drucker-Hilbert Co. 106 W. 43rd Street, New York 18, NY, Photo number 5722#3. Attached label says: "From Press Wireless, Inc. 1475 Broadway, N.Y., N.Y. PRESS WIRELESS HISTORY IN THE MAKING. Salvatore A. Barone, Chief Manufacturing Engineer, and Ray H. dePasquale, Director of Manufacturing, Press Wireless, Center, Turned the First Earth for the Foundations of the New Manufacturing Engineering Plant at 35th Avenue and 38th Street, Long Island City, July 16, 1945. Looking on and Applauding are Members of the Manufacturing and Engineering Staff." |

Direct radio news service was established between the US and The Netherlands soon after the establishement of PreWi's permanent office in Paris, with first contact on January 3, 1945. The station in The Netherlands operated under the call sign "PV", and it used equipment similar to that landed at Normandy.

The Manilla circuit had been shut down on December 31, 1941 upon the Japanese invasion, but was resumed on February 26, 1945. The new service between the Philippines and the US included radio telegraph, phone and facsimile modes.

In May 1945 PreWi established direct radio service between New York and Buenos Aires, Argentina, handling both press reports and government communications. This was the first radio link between the two countries and the fourth PreWi station in South America.

At the US government's request PreWi established a relay station in Tangiers, North Africa, to handle press and government traffic between Europe and America. Experience during the war had shown that North Africa was an ideal location for radio relay purposes. The government further promised the company that it could make use of war surplus material stockpiled in Europe.

Fergus Kerrigan, VP of the company, negotiated a loan from the Export-Import Bank to finance the Tangiers project. However, A. Warren Norton, president of the company, strongly opposed the project and declined the Bank's offer, but never gave a reason for his opposition. A group of executives in the company disagreed with Norton and took their case directly to the Board of Directors, arguing that failing to install the relay station would lead to a decrease in traffic and revenue. However, the Board supported Norton, and disallowed the loan and the installation. Mackay Radio subsequently received authorization for a relay station in Tangiers, and it was shown later that PreWi lost a considerable amount of revenue by turning down the government's offer.

Immediately after the Japanese surrender, PreWi opened an office in Tokyo, manned by Chester Ford. Ford had an amazing series of adventures during the Pacific campaign, having gone ashore with the invasion force at Leyte and in the Phillipines. An account of his war years is given in Press Wireless Signals Magazine, Vol III, No. 3.

This Signals issue was written right at the end of the war, and provides a remarkable picture of a large company operating at full bore, both on the manufacturing side and on the press traffic business. That, unfortunately, was about to come to an abrupt end.

The company obviously was pinning its post-war fortunes on the technology developed during the war, and by taking advantage of post-war news opportunities.

During 1946-1947 PreWi suffered significant financial losses because of reduction in press volume after the end of the war, and because of increased personnel expenses. Indeed, revenues dropped by nearly 2/3 during the one-year period. The company attempted to stem these losses by reducing operating expenses, including the shutdown of its brand-new radio equipment manufacturing operation on Long Island (which indirectly led to the founding of Technical Materiel Corp, as well as Northern Radio). It also asked the FCC for authority to handle press administrative and general deferred commercial traffic. There was considerable disagreement within the company about the rate structure proposed for these types of traffic, and evidently the FCC had some reservations about allowing the company to enter this business, denying the request.

A layoff of 46 operating staff in August 1946 led to a strike by members of the American Communication Association (ACA) union, and further, Western Union employees refused to relay copy from PreWi, though WU management continued to handle PreWi's traffic without delays for a time. Within days an embargo on international press messages went into effect to put further pressure on the company. The embargo was lifted on August 19, 1946, when the ACA agreed to arbitration with the company. The strike ended when the arbiter, Arthur Meyer, ruled that the company had to re-hire the 46 employees. Eventually the arbitration was settled in favor of Press Wireless, stating that it was within its rights to fire the employees.

This was a pyrrhic victory, however; the company's financial situation was so dire that it was forced to file for bankruptcy on August 15, 1947, and the filing was authorized the US Federal Court.

In 1957 the company moved its New York transmitting facilities from Hicksville to a 500-acre site at Centereach, Long Island, where it operated 47 high-power transmitters, though in the 50's the transmitters were built by Gates. The receiving site was moved to Northville.

Below is a photo of Press Wireless technicians viewing the signal from Russia's second earth satellite, called "Muttnik" on November 3, 1957. (Click on photo to see full-size image).

Press Wireless was acquired by ITT in 1965. At the time, D.K. deNeuf was president of the company. deNeuf had joined PreWi in 1930 as a Vice President, left the company to become general manager of Northeast Radio Corp, and rejoined PreWi in 1957 as Executive VP, becoming President in 1963.

Press Wireless was still in the broadcast business, at least as late as the mid-60's, as indicated by this QSL to a SWL in Sweden:

Press Wireless Manufacturing Company was incorporated in 1941 in Massachusetts under the original name Milliken Machine Company, with all operations located in a plant in West Newton, Mass. The facilities of the former Press Wireless Manufacturing (PWM) Corporation of Hicksville, Long Island were acquired in 1948 and Milleken's corporate name was changed to Press Wireless Manufacturing Company, Inc.

In 1952 the controlling interest in PWM was acquired by La Pointe Electronics, Inc and the facilities of the Hicksville Division were moved to a more spacious plant in Rockville, Connecticut. The plant was adapted to the quantity production of electronic and precision electro-mechanical parts and equipment.

Press Wireless Manufacturing's two plants (West Newton, MA and Rockville, CT) and their facilities, equipment, and products are described in a brochure "Facilities of Press Wirelss Manufacturing Company".

Below is a scan of PWM's very classy stationery and envelope (kindly provide to me by Duncan Brown K2OEQ from the Antique Wireless Museum's archives):

|

|